Locked Up and Dying

California jails are holding fewer people than they have in decades, but they are deadlier places than ever. The number of people dying surged during the COVID-19 pandemic. Then a wave of overdoses and suicides kept death rates at record levels. “The vast majority of these deaths are preventable,” one expert said. Almost all of the people who died in the lockups had yet to be tried.

California’s elected leaders are aware of the crisis in county jails. Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2019 pledged to make them safer places by working through the state’s jail oversight board. He signed a law last year that forces jails to disclose more information about deaths behind bars. But the death rate in California jails remains well above the level that caught the governor’s attention five years ago. Sheriffs who oversee the facilities say they’re struggling to keep fentanyl outside of their jails as arrested suspects and even county employees smuggle them inside.

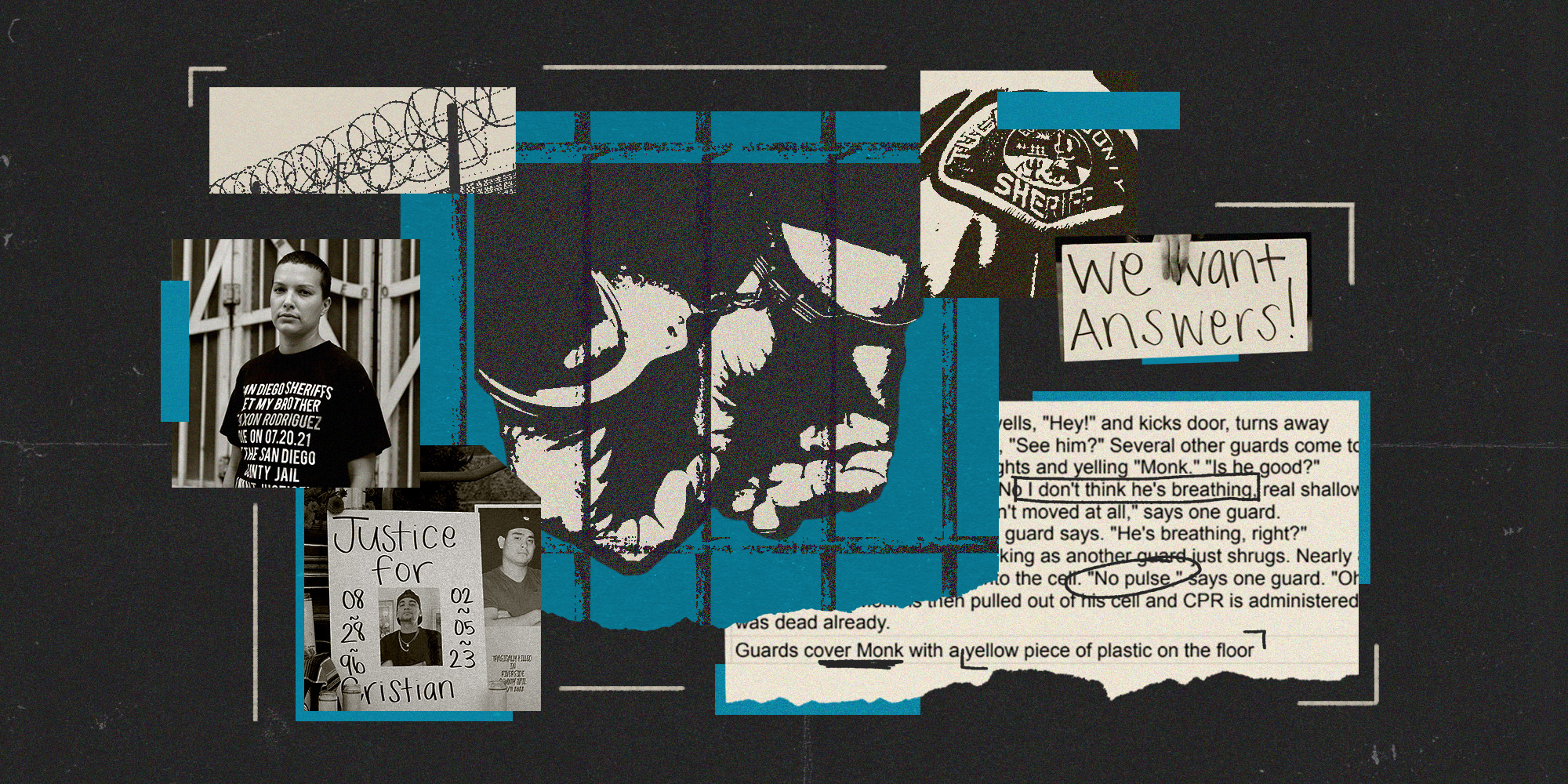

Many families of deceased inmates want to see more dramatic changes. They’re pressing sheriffs to more rigorously scan jail employees for contraband, asking district attorneys to prosecute jail staff over fatal incidents, and urging local governments to turn more authority over to public health officials. “The whole time, he needed medical care and they just ignored him,” said Lisa Matus, whose son died from a fentanyl overdose in a Riverside County jail in August 2022. An autopsy showed serious blockages in an artery that fed his heart, a condition that his autopsy indicates went untreated during his confinement.

“Locked Up and Dying,” an ongoing investigation by CalMatters reporters Nigel Duara and Jeremia Kimelman, explores the increase in deaths among California jail inmates and the state’s attempts to reverse the trend. Feature photography by Kristian Carreon, Adriana Heldiz, Jules Hotz, and Larry Valenzuela. Production by Liliana Michelena.